This post is a follow up to my previous post on the Struts’ RCE CVE-2018-11776. In this post, I’m going to go through the discovery of the vulnerability in more detail, and show exactly how remote user input from an http request ended up being evaluated as an OGNL expression. This post relies heavily on the CodeQL for eclipse plugin which allows you to visualize the flow path of the tainted data.

[EDIT]: Path exploration is now available on LGTM. You can also use our free CodeQL extension for Visual Studio Code. See installation instructions at https://securitylab.github.com/tools/codeql/.

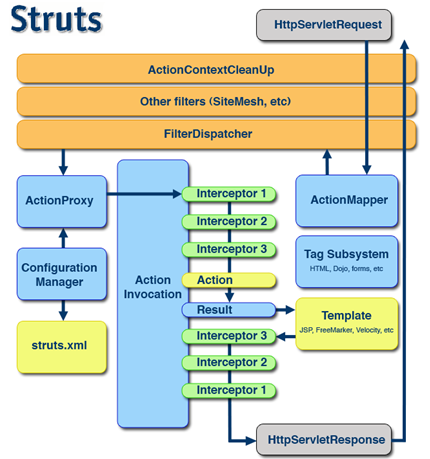

The architecture of Struts

To begin with, I’ll first briefly explain how Struts processes an http request. The following figure comes from the Struts’ documentation:

Roughly speaking, when Struts receives an http request, it’ll first use the pre-configured ActionMapper to construct an ActionMapping which contains information such as namespace, actionName, method and params from the request. This ActionMapping then gets passed into the Dispatcher, in which an ActionProxy and ActionInvocation are created. These classes then delegate the work to the appropriate Action and Result class to process the request. In this post, we’ll follow the http request through this labyrinth, and see how various elements of the request end up getting evaluated as OGNL.

Taint-tracking from first principles

This time I’ll start taint-tracking from the incoming HttpServletRequest and I’ll show how it ended up in the namespace field of ActionProxy. As well as making it more clear how the namespace property got tainted, the query this time will also be more general, and is able to identify other previous OGNL injection problems. The initial query I used for taint tracking this time can be found here. I’ve made some improvements to the custom dataflow library and included tracking through various methods in subclasses of Collections. It should be clear what they do from the documentation in the CollectionEdges.qll and ExtraEdges.qll libraries. Many of the edges and sanitizers are reused from the query I used in my previous post. As you can see, by using CodeQL libraries, I can reuse and share code between queries, which means things get easier and easier as you go along.

Let’s now take a closer look at the various components of this DataFlow::Configuration. First, let’s take a look at the source, which specifies where the user input comes from. The standard CodeQL library provides a class called RemoteUserInput, which represents inputs that are likely to be untrusted. This class is usually good for general purpose taint-tracking, and it contains various sources from the HttpServletRequest class. When hunting vulnerabilities, I also like to extend it to include more sources, so I added this to the dataflow_extra library:

/** Extra remote sources that comes from `ServletRequest`.*/

predicate extraRequestSource(DataFlow::Node source) {

exists(Method m, MethodAccess ma | m.getName().matches("get%") and

not (m.getName() = "getAttribute" or m.getName() = "getContextPath") |

(m.getDeclaringType().getASupertype*().hasQualifiedName("javax.servlet.http", "HttpServletRequest")

or m.getDeclaringType().getASupertype*().hasQualifiedName("javax.servlet", "ServletRequest"))and

source.asExpr() = ma and ma.getMethod() = m

)

}

which basically treats anything that looks like a getter as a source, with the exception of getAttribute and getContextPath, which are usually set from the server side. This gives me these sources:

override predicate isSource(DataFlow::Node source) {

source instanceof RemoteUserInput or extraRequestSource(source)

}

For the sink, I used isOgnlSink from last time.

For the additional flow steps, I used this:

override predicate isAdditionalFlowStep(DataFlow::Node node1, DataFlow::Node node2) {

standardExtraEdges(node1, node2) or

collectionsPutEdge(node1, node2) or

taintStringFieldFromQualifier(node1, node2) or

isTaintedFieldStep(node1, node2)

}

The first two edges, standardExtraEdges and collectionsPutEdge are general purpose edges used for tracking collections. I decided to reuse the isTaintedFieldStep from last time here. Recall that this edge is there to track cases like this:

public void foo(String taint) {

this.field = taint;

}

public void bar() {

String x = this.field; //x is tainted because field is assigned to tainted value in `foo`

}

As explained before, this can lead to spurious results if the tainted field is accessed before it was assigned. I decided to include this because from looking at the architecture of Struts, I saw that tainted data from an http request are first used to create ActionMapping and ActionProxy, and the tainted fields from these objects are then accessed later in the lifecycle to perform an action. So the assumption that this edge makes seems valid for the problem I am considering.

Finally, I also added the taintStringFieldFromQualifier edge:

/** Tracks from tainted object to its field access when the field is of type string.*/

predicate taintStringFieldFromQualifier(DataFlow::Node node1, DataFlow::Node node2) {

taintFieldFromQualifier(node1, node2) and

exists(Field f | f.getAnAccess() = node2.asExpr() and f.getType() instanceof TypeString)

}

The CodeQL dataflow library actually has fairly precise capability of taint-tracking through field assignment and access (thanks to the hard work of Anders Schack-Mulligen). For example, by default, this is tracked:

DataType x;

x.setFieldA(a); //<-- a is tainted

String a1 = x.getFieldA(); //<-- now a1 is tainted

String b = x.getFieldB(); //<-- b is not tainted.

However, in order to keep the tracking precise, a field is only considered tainted when the analysis is able to find an explicit assignment that assigns tainted data to that particular field. This means that a field from a tainted source may not be considered tainted by default, for example:

HttpServletRequest request;

Part part = request.getPart("part"); //<-- source

String name = part.getName(); //<-- name not tainted because there was no explicit assignment to the name field

This is a fair assumption because fields from a source may not always be tainted, for example:

ActionProxy proxy; //<-- source

ActionConfig config = proxy.getConfig(); //<-- not tainted.

So I need to tell CodeQL explicitly when a field from the source should be considered tainted. I can use taintStringFieldFromQualifier to help me do this. By using this, I am saying that I want any field access to be tainted if the object itself is tainted, but I only want it to do this if the field is of type string. The rationale behind this is to make all field accesses from a source tainted, but because at the source level, user input usually comes in as string, I only want this to happen when the field that is being accessed is of type string. This doesn’t restrict the field access to the source and may give me more results than I need, but it is simple and good enough for my purpose.

Next the sanitizers.

override predicate isBarrier(DataFlow::Node node) {

node instanceof StrutsTestSanitizer

or

ognlSanitizers(node)

or

node instanceof ToStringSanitizer

or

node instanceof MapMethodSanitizer

}

I reused the ToStringSanitizer and MapMethodSanitizer from last time, but I extended it to cover all object and map types, as I’ve since discovered a few more overrides of these methods in Struts that gave me bogus results. The StrutsTestSanitizer excludes code that is in test code, and the ognlSanitizers take the various sanitizer methods like callMethod, cleanupActionName and cleanupMethodName that fixed s2-032, s2-033 and s2-037 into account.

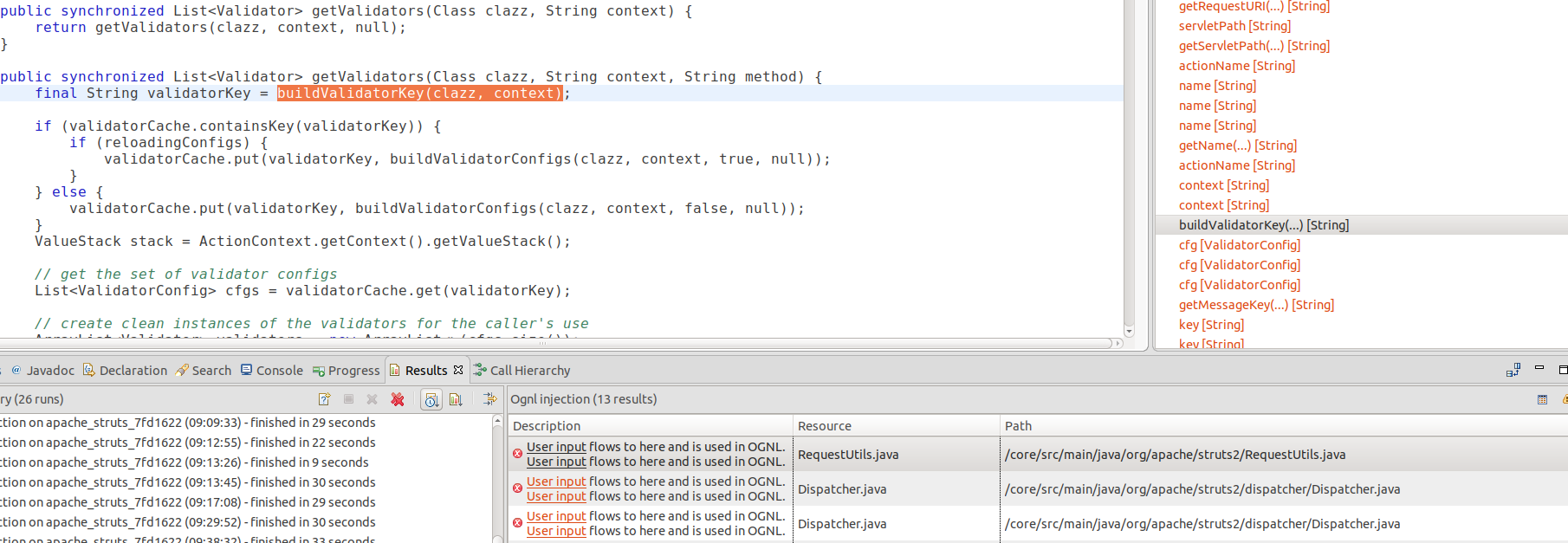

Running this query, I got 13 results.

Looking at the dataflow path, I noticed that many of them go through a method called getValidators:

public synchronized List<Validator> getValidators(Class clazz, String context, String method) {

final String validatorKey = buildValidatorKey(clazz, context); //<-- context tainted

if (validatorCache.containsKey(validatorKey)) {

if (reloadingConfigs) {

validatorCache.put(validatorKey, buildValidatorConfigs(clazz, context, true, null));

}

} else {

validatorCache.put(validatorKey, buildValidatorConfigs(clazz, context, false, null));

}

ValueStack stack = ActionContext.getContext().getValueStack();

// get the set of validator configs

List<ValidatorConfig> cfgs = validatorCache.get(validatorKey); //<-- fetch configuration with validator key, taint now goes to cfgs

The tainted context is used here as a key to fetch the cfgs object from a cache. Unless an attacker can also control the content of this cache, it is unlikely that cfgs would contain anything that could cause OGNL injection. So I add a sanitizer to filter out this result:

exists(MethodAccess ma, FieldAccess fa | ma.getMethod().hasName("get") and

ma.getQualifier() = fa and fa.getField().hasName("validatorCache") and

fa.getField().getDeclaringType().hasName("DefaultActionValidatorManager") and

node.asExpr() = ma

)

After inspecting some other paths, I added two more sanitizers to exclude paths that are unlikely to be hit:

/** Filters out the internals of `ActionContext`, which are unlikely to be of user control.*/

predicate actionContextSanitizer(DataFlow::Node node) {

exists(MethodAccess ma, Method m | ma.getMethod() = m and m.getDeclaringType().hasName("ActionContext") and

m.hasName("get") and node.asExpr() = ma

)

}

/** Filters out the cases where `RestfulActionMapper` is used.*/

predicate restfulMapperSanitizer(DataFlow::Node node) {

node.asExpr().getEnclosingCallable().hasName("getUriFromActionMapping") and

node.asExpr().getEnclosingCallable().getDeclaringType().hasName("RestfulActionMapper")

}

/** Filters out cases where jsp file is exposed. */

predicate tagUtilsSanitizer(DataFlow::Node node) {

node.asExpr().getEnclosingCallable().getDeclaringType().hasName("TagUtils") and

node.asExpr().getEnclosingCallable().hasName("buildNamespace")

}

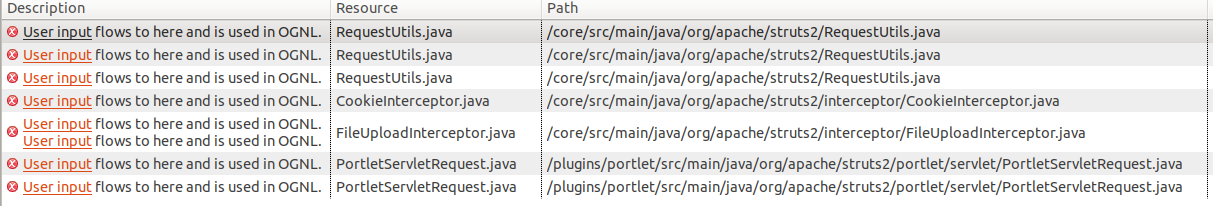

The exact reason for excluding these came after close inspection of the code path, and is beyond the scope of this article. If you would like to discuss this, please feel free to ping me at @mmolgtm. After adding these sanitizers to clean up the results, I now got 7 results with the final query.

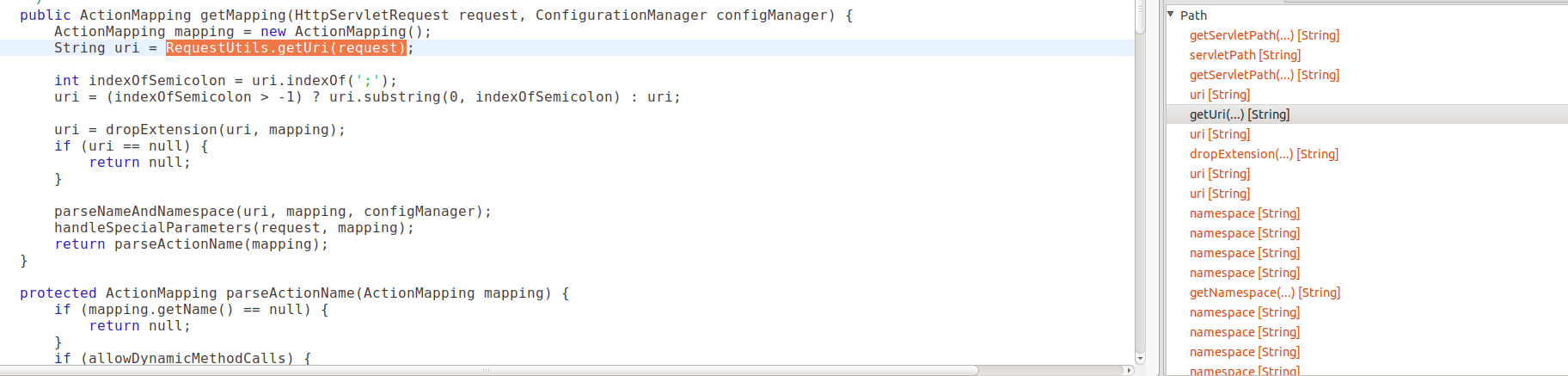

Let’s now take a closer look at the results. Clicking on the first result, I see that after a few steps, I landed in the getMapping method in DefaultActionMapper:

As explained before, this happens in the early stage of the lifecycle, where an ActionMapper uses the incoming HttpServletRequest to create an ActionMapping. Clicking through a few more steps, I enter into the parseNameAndNamespace method:

protected void parseNameAndNamespace(String uri, ActionMapping mapping, ConfigurationManager configManager) {

String namespace, name;

int lastSlash = uri.lastIndexOf('/'); //<-- url tainted

if (lastSlash == -1) {

....

} else if (alwaysSelectFullNamespace) {

// Simply select the namespace as everything before the last slash

namespace = uri.substring(0, lastSlash); //<-- namespace taken from uri!

name = uri.substring(lastSlash + 1);

} else {

....

}

....

mapping.setNamespace(namespace); //<-- namespace tainted

mapping.setName(cleanupActionName(name));

It now becomes clear why the alwaysSelectFullNamespace has to be true for the application to be exploitable. Looking at how namespace is set in this function, this is the only branch where namespace is taken from the user controlled uri.

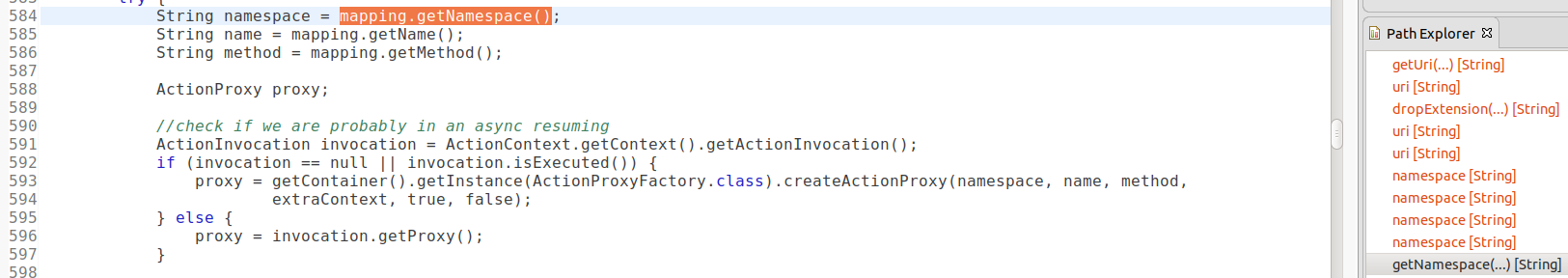

Following the tainted data a few more steps, I ended up in the Dispatcher:

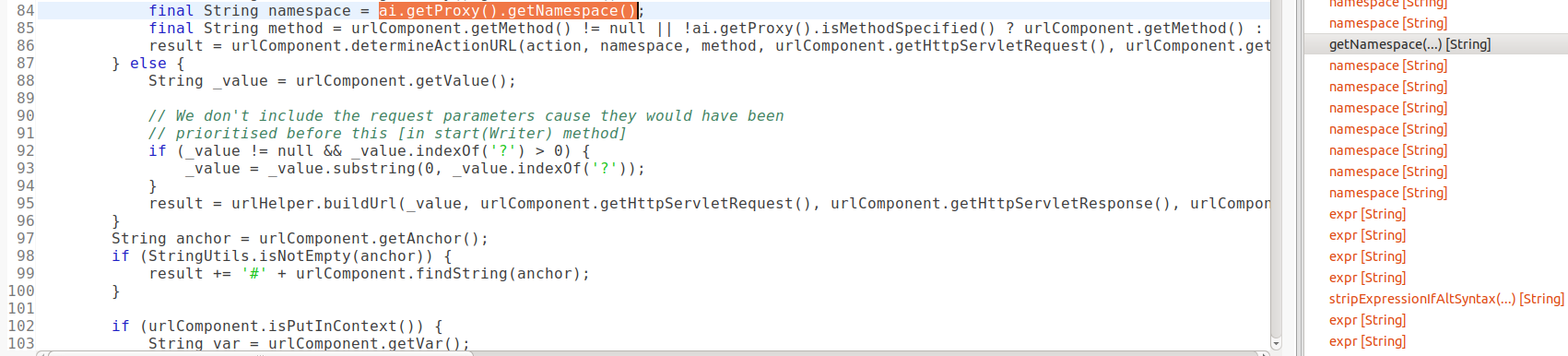

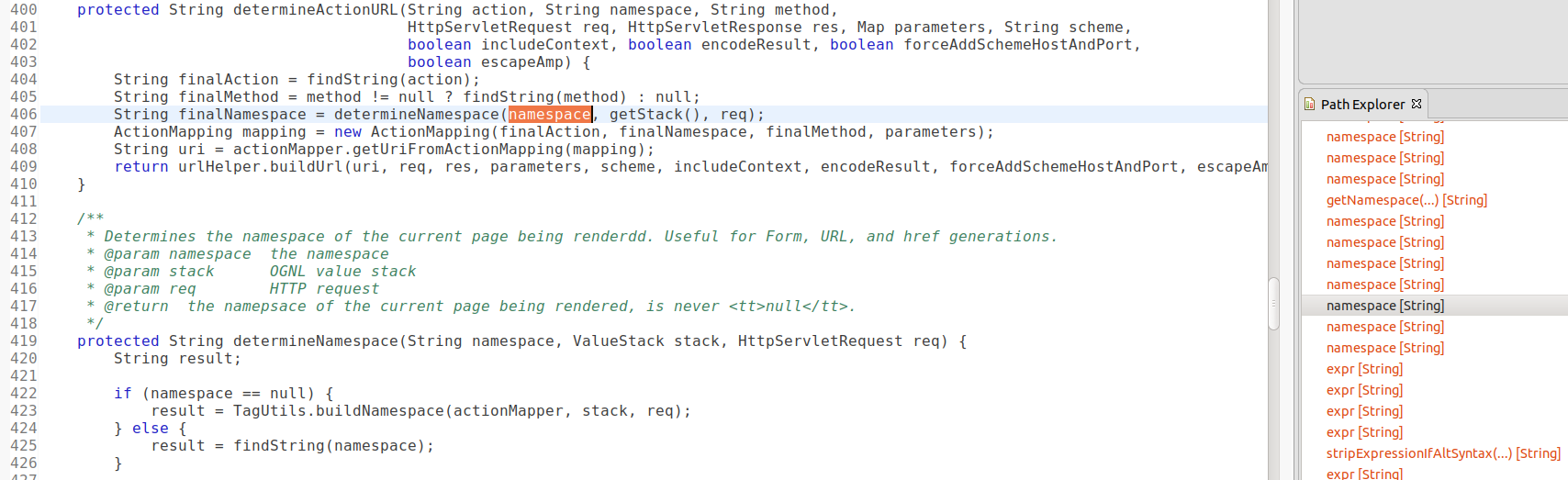

Recall from the architecture overview that this is the stage where the Dispatcher creates an ActionProxy from the ActionMapping. As I can see from line 584 that namespace is taken from the ActionMapping and in line 593, it is used to construct the ActionProxy. From now on, I can assume that the namespace field of an ActionProxy may be tainted, which was the assumption that I made in the previous post. The remaining flow steps now just follow the ones in the previous post. For example, after clicking into the next getNamespace in the path explorer, I see that the ActionProxy is now being used in the corresponding Result to process the request.

The namespace here then goes into determineActionURL in line 86, which then goes into findString in line 425, which evaluates namespace as an OGNL expression under the hood.

I’ve just walked through the entire lifecycle of an HttpServletRequest in Struts, without even running it. Moreover, by using dataflow analysis, I am essentially looking at many flow paths at the same time and I’m able to identify issues with different Struts configurations.

One caveat of path explorer is that, by default, only 4 paths are shown. To see more paths, you can either change the preference in eclipse with Window->Preferences->QL->Advanced and check the enable advanced options box to change it under Maximum number of paths per alert, or you can filter out some results that you have already seen. I’ve included a sanitizer in the query for filtering out known results:

/** Filters out results that we've already seen, use and modify this to highlight results in different files.*/

predicate knowResultsSanitizer(DataFlow::Node node) {

node.asExpr().getFile().getBaseName() = "ServletUrlRenderer.java"

or

node.asExpr().getFile().getBaseName() = "PostbackResult.java"

or

node.asExpr().getFile().getBaseName() = "ActionChainResult.java"

or

node.asExpr().getFile().getBaseName() = "ServletActionRedirectResult.java"

or

node.asExpr().getFile().getBaseName() = "PortletActionRedirectResult.java"

}

Add this to the isBarrier predicate and comment out the appropriate lines to see results that you haven’t seen before.

Bonus material

Looking through the list of results, I see that apart from the ones in CVE-2018-11776, there are some other interesting ones:

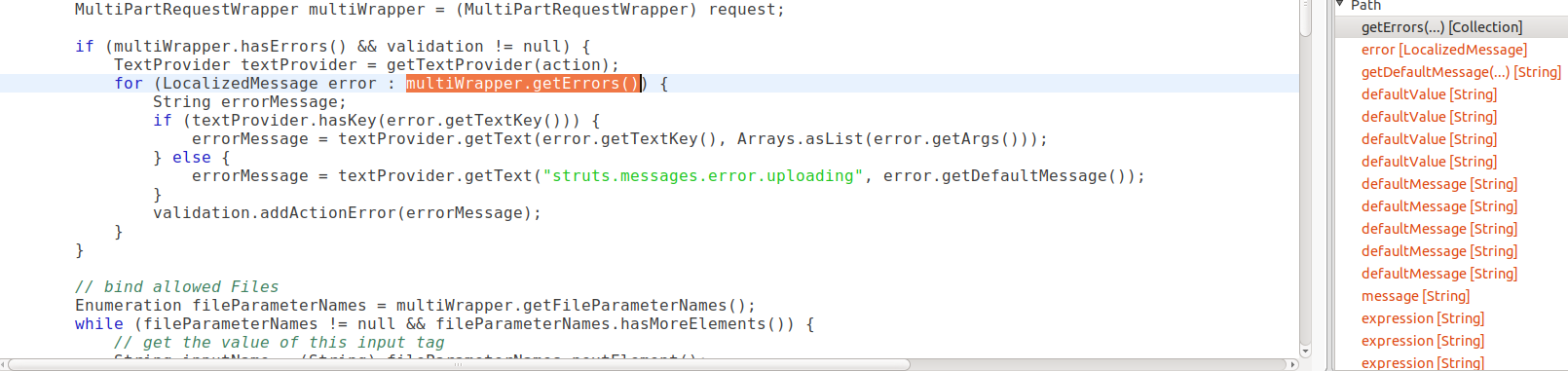

FileUploadInterceptor should be no stranger to people who follow vulnerabilities in Struts. Probably the most severe vulnerability in Struts in recent years, S2-045 affected this interceptor. Let’s take a look at it:

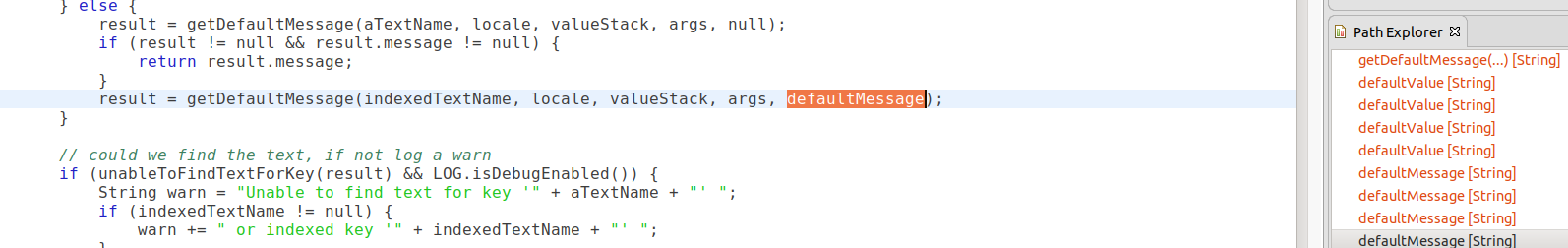

I see that I started out with multiWrapper.getErrors. Here, multiWrapper is of the class MultiPartRequestWrapper, which is a subclass of HttpServletRequest. The getErrors method is an override method which is used to store any errors that occur while the request is being processed, and is likely to contain user controlled data. The error object comes from this and then gets passed into the textProvider.getText method. After getting passed around a few times, it is then entered into the getDefaultMessage method

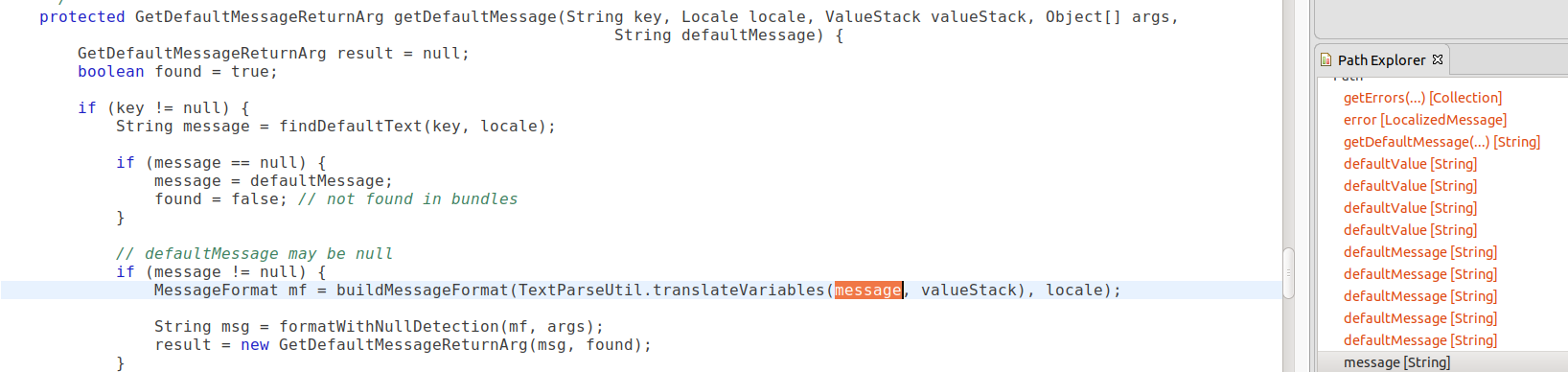

A few steps later, it ended up in the translateVariables method

which evaluates message as an OGNL expression under the hood. The result is still here because the fix to the issue involved sanitizing user input before creating the MultiPartRequestWrapper object that I used as a source.

The other result in the CookieInterceptor is one of the issues fixed in S2-008. The reason that it is showing up here is because I didn’t add the isAcceptableName method as a sanitizer in my query. The flow path is not too complicated and I’ll not go through it here, but do take a look at it on the path explorer.

Conclusions

In this post I’ve shown how CodeQL is capable of tracking user input in Struts all the way from an incoming HttpServletRequest to an OGNL evaluation. By using the dataflow library with CodeQL, I’ve written a query that follows the lifecycle of an HttpServletRequest in Struts. On top of that, the query gave me 7 results, of which 5 correspond to real RCE vulnerabilities in the past. In total, this query found these RCEs: s2-008 (part), s2-032, s2-033, s2-037, s2-045, s2-057. The queries, as well as the libraries used in this post have been uploaded to this git repository and many of the libraries there can be also reused for writing your own analyses. Happy bug hunting with CodeQL!

Note: Post originally published on LGTM.com on September 24, 2018